The Endurance Expedition to Antarctica. In 1914, a strange ad appeared in London newspapers. In 1911, Norway’s Roald Amundsen succeeded in reaching the South Pole

The text read, “Men are needed for a dangerous journey. Low wages, extreme cold, months of absolute darkness, constant danger, uncertain return. Honors and recognition if successful.” The ad was from Sir Ernest Schackleton, a well-known polar explorer, who was looking for the right people to make the first crossing of the Antarctic continent in dog sleds. As many as 5,000 people responded to the ad. In those days, people passionately followed polar expeditions. The Poles were the last remaining lands to be discovered, and there was a lot of competition among explorers to star in memorable adventures.

Schackleton was no stranger to this kind of venture. He had previously participated in the Antarctic Discovery expedition, led by Robert Falcon Scott, from which he had to return early for health reasons. Then in 1909, with his own expedition, he succeeded in reaching the southernmost point ever reached by man, only 180 km from the South Pole, and thanks to this feat, he was knighted by King Edward VII of England.

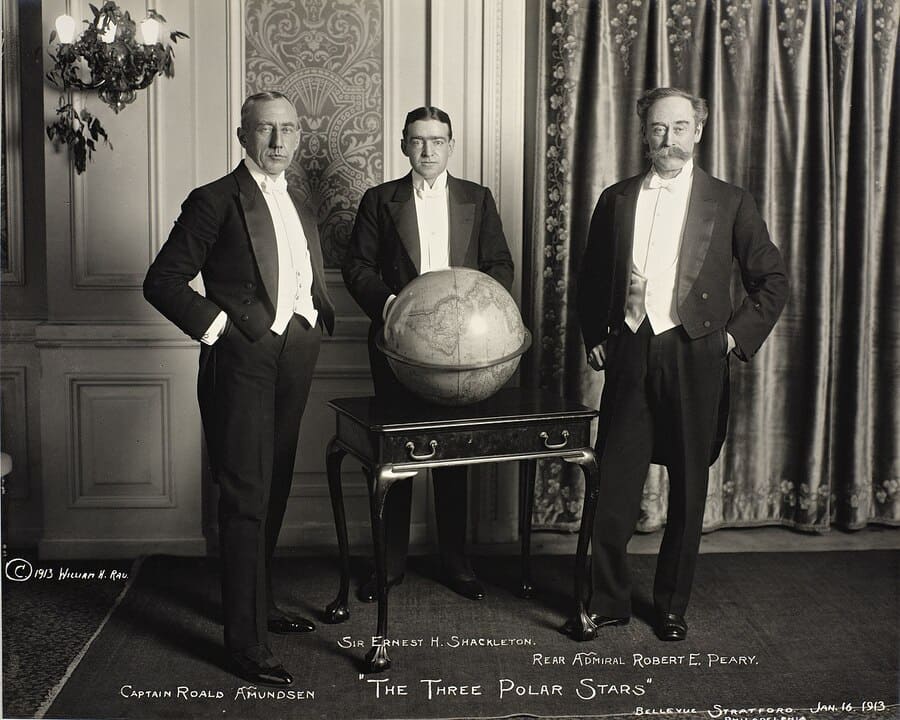

In 1911, Norway’s Roald Amundsen succeeded in reaching the South Pole first, after traveling more than 1,400 km in terrible conditions, preceding Britain’s Robert Falcon Scott by several days. The competition for this important record having therefore ended, Schackleton thought of launching an expedition of his own, which he called the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which aimed to cross the continent of Antarctica, from one side to the other, between 2,500 and 3,000 km depending on the size of the ice shelf.

He set to work to find sponsors for the venture. He embarked on a wide lecture tour around the world. Due to its popularity, he raised enough money to organize two ships that would have a crew of 28 people each.

The Endurance Departs to the Sea of Weddel

The ships were named Endurance and Aurora. The Endurance was a brig of three masts and one funnel as it also had steam propulsion. The expedition also wanted to establish a scientific base to study climate, terrestrial and marine fauna, and hydrographic and geological work. For this, there was on board also a meteorologist, geologist, doctor, veterinarian a photographer and other professionals. Also traveling on the Endurance were 66 sled dogs and some cats.

The Endurance left England in August 2014, and Schackleton reached it when he was in Buenos Aires as he had lingered in London, where he had met the expedition`s last financiers.

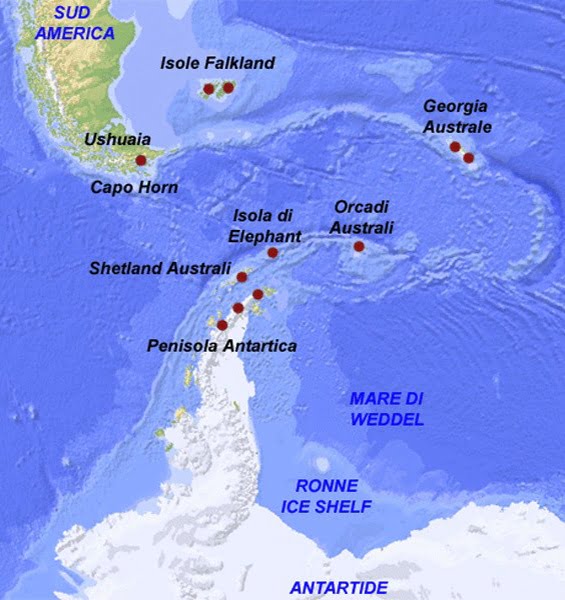

They set course for South Georgia and from there, on December 5, 2014, they sailed into the Weddel Sea, which lies on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

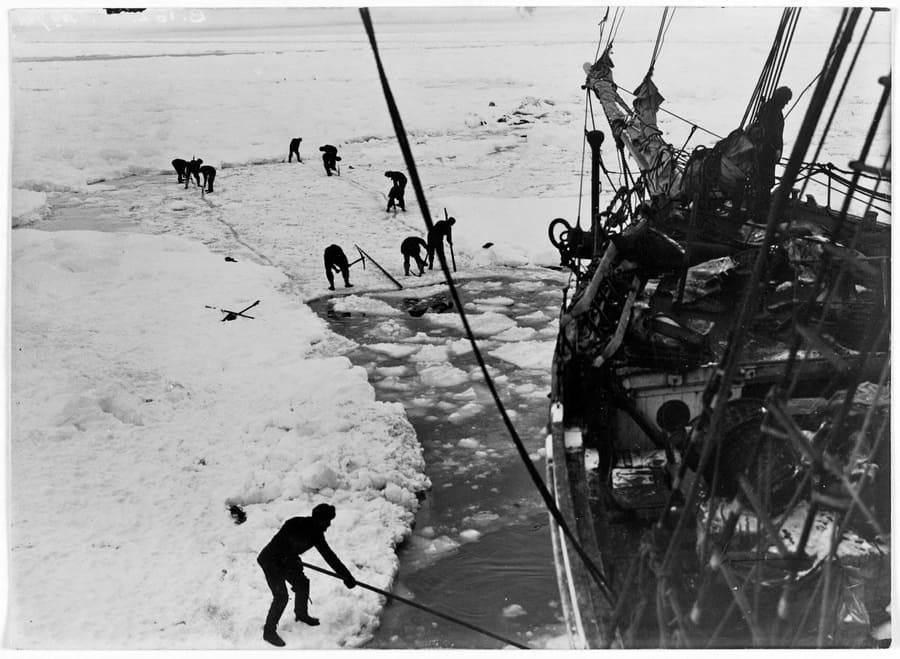

Already in the first few days, navigation was difficult because of the ice blocks floating on the water. The bow of the Endurance sometimes managed to clear a path, but the ice floe was getting thicker and thicker. The ship avoided large icebergs more than 100 feet high, but it had to slow down and more and more crewmembers had to descend onto the ice floe with picks and iron poles to break through the ice. Until on January 19, 2015, the Endurance was completely stuck in the ice. All attempts to free the ship had been unsuccessful. It was impossible to remove the ice, which was several meters thick.

Schackleton at this point thought it would be better to wait for the less cold season that would allow the Endurance to be freed from the ice. It was not to be, however. On February 24, 2015, it appeared clear that it would not be cleared of ice and would have to wait until next spring.

Ice floe crushes the Endurance

Schackleton decided to convert the ship into a winter shelter. The pack in which the ship was stuck was of immense size. In the following months, ice movements began to crush the Endurance by breaking through the hull, and the ship began to take on water.

It was decided to abandon the ship and a camp was set up on the ice floe. The Endurance’s three lifeboats were recovered. The ship sank a little more each day, until on November 21, 2015, the Endurance sank completely and disappeared from view.

The situation of the Endurance’s crew was not good at all. They were on an ice floe drifting in the Weddel Sea. Food was beginning to run short and survival conditions were extreme. Wind gusts of 100 miles per hour and temperatures that could drop to minus 35 degrees made living conditions extremely unbearable. Food supplies were thinning, and even the supply of coal, with which they heated themselves and turned ice into drinking water, was being depleted. The only alternative food available came from the seals and penguins that could be caught.

The ice shelf was about 100 km from Paulet Island. Schackleton thought he could reach it by walking on the ice shelf, but the very irregular ice formation did not allow for transit. Until finally on 09 April 2015 the ice broke and they could put the three lifeboats overboard. They sailed north; in 7 days of navigation, they covered 750 km and arrived at Elephant Island. It is an uninhabited island, far from the shipping lanes, but at least, they were now on dry land for the first time in 497 days instead of on a drifting ice floe.

The Odyssey to get to South Georgia

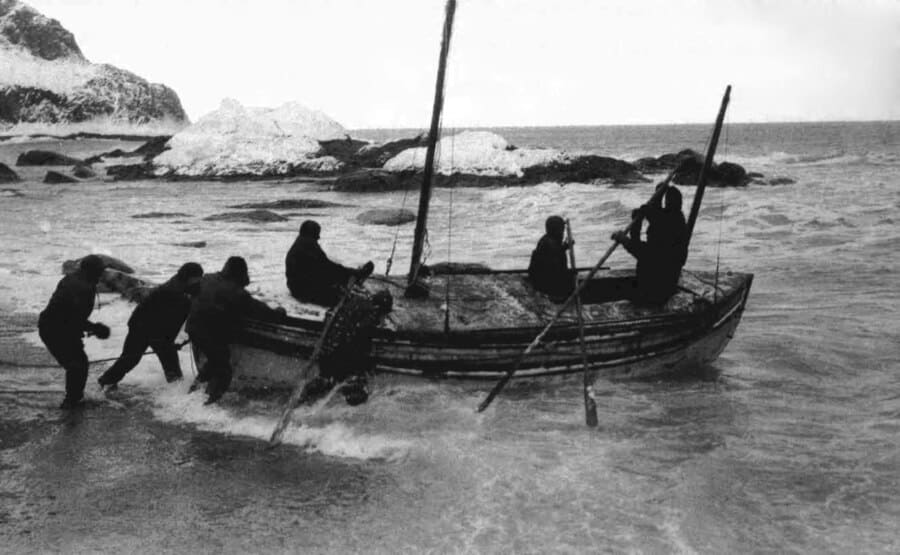

After a few days of rest, Schackleton decided to organize a rescue operation that was probably one of the greatest nautical feats of all time: setting off in a lifeboat and reaching South Georgia for help.

Work began to condition the 20-foot-long lifeboat on which Schackleton would travel along with his first officer, the carpenter, and three experienced sailors. Food was prepared that they would consume during the trip, consisting mainly of penguin meat. The carpenter made some changes to the lifeboat, raising the edges and building a cover under which to find shelter from the wind and water. The distance to be covered from Elephant Island and South Georgia was a full 1,300 kilometers in one of the roughest stretches of sea in the world, where winds can reach 300 km/h and waves are more than 20 meters high.

They set sail on April 24 and, thanks to the First Mate’s great skill in the use of the sextant, sighted South Georgia’s San Pedro Island on May 8, but strong winds prevented the boat from approaching the island, on pain of crashing onto the rocks. They spent two horrible days and nights in the billows waiting for the storm to subside and finally were able to land on a deserted beach on the south side of the island, on the verge of a nervous breakdown. But unfortunately, that side of the island was deserted, and the whaling center where Schackleton planned to call for help was on the north side of the island.

No longer able to use the boat that had been damaged by two days and two nights of stormy weather, Schackleton decided to walk the nearly 50 km of mountains and glaciers across the island to the other side. It was an extremely difficult route that no one had ever done.

The climb between the glaciers of South Georgia

Three sailors remained on the beach while the other two accompanied Schackleton on the venture. They set out to cross the mountains, with no proper equipment, no alpine training and no map to cross the island and reach the whaling station.

Incredibly, In 36 hours they managed to cover the rough and dangerous 50 km distance that separated them from the whaling center.

When Schackleton appeared before the head of the whaling center, the latter could not believe his eyes. The story of Schackleton’s expedition was well known, but the common opinion was that he and his men were dead.

Shackleton sent for the three men who had remained on the other side of the island and set to work organizing the rescue of those left on Elephant Island. This last rescue was not so easy because of the ice that prevented access to the island, 3 times, it was not possible to get close. Therefore, Shackleton asked the Chilean government for help, which sent a special ship called an escampavía serving in the Chilean Navy, accompanied by a British whaling ship. Finally, on August 30, 1916, as they approached Elephant Island, Shackleton jumped on the launch heading for the coast and began counting the figures rushing onto the beach and shouting, “They’re all there! They’re all there!” In fact, everyone had miraculously survived; there were no casualties among the crew.

The Chilean ship accompanied Shackleton and his group to the town of Punta Arenas. However, for Shackleton it was not over yet. It had come to his attention that the expedition’s other ship, the steamer Aurora, had had some serious problems. The Aurora, based in Australia, was tasked with docking on the other side of the Antarctic continent, in McMurdo Strait, to set up supply points in the second half of the crossing.

Aurora also is caught in ice

One day in a severe storm when the ship was anchored at the Cape Evans base on Ross Island, it was torn from its mooring and pushed out to sea where it became trapped in the ice. At that time, only 18 crewmembers were on the ship while the other 10 were ashore. The majority of the supplies and fuel were on the ship, but for those who remained ashore, fortunately there were supplies to be stored on the crossing route.

The Aurora, after drifting in the ice for more than 2,600 km, managed to break free and although in poor condition, finally reached New Zealand. Schackleton then traveled to New Zealand, had the Aurora repaired, and organized the rescue of the 10 remaining crewmembers on Ross Island.

On January 10, 1917, Schackleton on the Aurora arrived at Cape Evans. They found only 7 of the 10 crewmembers. The chaplain who was also the Aurora’s photographer had died falling into a crevasse in the ice. Two other crewmembers had drifted away from camp when a snowstorm surprised them, and they were never heard from again.

Thus ended the Imperial Trans-Arctic Expedition. The crewmembers had been isolated for 3 years, and only then did they learn that World War I had broken out in Europe. Upon returning home, news of the war excelled in the newspapers, reasoning that the veterans of the expedition, did not receive much attention. Most, including Shackleton, entered the army, and 3 of them died in the war.

Death catches Schackleton at the beginning of a new adventure

The Endurance odyssey has remained so mythical because this adventure was captured by Australian photographer Franck Hurley, who was Endurance’s on-board photographer. Hurley would leave behind hundreds of photographs, some quite exceptional, that almost allow us to relive the expedition. Over the years, the Endurance’s adventure inspired dozens of books and a television series.

When the war ended, Schackleton organized another Antarctic expedition, with the ship Quest. But sadly, he died suddenly of a heart attack while the ship was moored in South Georgia on January 5, 1922, at only 47 years old. According to the instructions of Schackleton’s wife, he was buried in South Georgia, where his grave can still be visited today.

Reinhold Messner retraces Schackleton’s route

In 2000, three of the world’s best-known climbers wanted to retrace on foot the crossing of San Pedro Island, South Georgia, where Shackleton had landed. Reinhold Messner, Steven Venables and Conrad Anker took to the same beach where Schackleton had landed with his sailors.

According to Messner, the crossing has true mountaineering value, as they had to cross four passes between 1,000 and 2,000 meters, among dangerous glaciers and horrible crevasses. Also incredible is the fact that they managed the feat in only 36 hours. Had they stopped, they would have frozen to death. Instead, Messner and his two companions crossed the mountain range in 3 days, bivouacking at high altitude and feeding themselves adequately. Moreover, the feat of Schackleton and his companions takes on even more value knowing that they did not lose their bearings and, despite having only leather boots and no special equipment, managed to reach their goal.

2022: Wreck of the Endurance found

In March 2022, the wreck of the Endurance, the approximately 44-meter three-masted ship that sank after being crushed by Antarctic ice, was located. The discovery was made by the Endurance22 expedition, funded by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust, which reportedly received an anonymous donation of 10 million euros to find the Endurance. After a failed attempt in 2019, British archaeologist Mensun Bound finally located the famous brig, thanks to the coordinates the expedition’s First Officer had left behind. The Endurance was found only 7.5 kilometers away from the indicated point, and it is thought that the difference in position is due to the coordinate calculation practiced at the time that would have underestimated the drift of the ice floe.

The wreck is located at a depth of 3008 meters and is in perfect condition. It will not be brought to the surface, instead it will be guarded and no objects are allowed to be touched or taken from the wreck.