Contents

Bir Tawil is a unique place in the world—an area of about 2,060 square kilometers located between Egypt and Sudan, yet claimed by neither country

This status as terra nullius—a Latin term meaning “no man’s land”—makes Bir Tawil a geopolitical rarity, shared only with a few other regions on the planet, such as Marie Byrd Land in Antarctica.

But how did this forgotten territory come into existence? Its history is intertwined with the legacy of British colonial rule, territorial disputes between Egypt and Sudan, and a series of administrative decisions that left Bir Tawil in legal limbo.

To understand the origins of Bir Tawil, we must go back to the late 19th century, a time when much of Africa was under European colonial rule. In 1899, the United Kingdom exerted significant influence over both Egypt and Sudan, two territories that, although formally distinct, were jointly administered under the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (also known as Anglo-Egyptian Sudan).

This arrangement stemmed from a series of complex events. Egypt, nominally part of the Ottoman Empire until 1882, had effectively become a British protectorate, while Sudan had been reconquered by the British after the Mahdist uprising.

In 1899, the British decided to establish a clear boundary between the two territories under their control. This political border was drawn along the 22nd parallel north, a straight line cutting across the eastern Sahara Desert. According to this demarcation, everything north of the parallel belonged to Egypt, while everything south—including the area we now know as Bir Tawil—was assigned to Sudan.

To the east of Bir Tawil, the Hala’ib Triangle—a larger, strategically important region on the Red Sea—was placed under Egyptian administration. This decision seemed straightforward and final: a geometric line drawn on a map to separate two regions under British influence.

However, as often happens with colonial borders, the reality on the ground was far more complex. Local tribes, such as the Ababda and Bishari, did not live according to the lines drawn by colonial administrators. Instead, they followed traditional routes linked to grazing, trade, and their cultural practices. This led to a revision of the border.

The 1902 Revision: An Administrative Border

In 1902, just three years after the initial agreement, the British realized that the 1899 border did not accurately reflect how local populations used the land. They therefore introduced a new administrative boundary, reassigning certain areas based on practical needs and tribal affiliations.

This change was driven by two main factors: the tribes’ cultural and geographical proximity and the need to simplify administrative management.

Bir Tawil, a desert area south of the 22nd parallel, was primarily used as grazing land by the Ababda tribe, whose base was near Aswan in Egypt. For this reason, the territory was placed under Egyptian administration.

Conversely, the Hala’ib Triangle, located northeast of Bir Tawil and both geographically and culturally closer to Khartoum (the Sudanese capital), was placed under Sudanese administration. This new boundary was no longer a straight line but an irregular border forming two distinct areas: the quadrilateral of Bir Tawil and the Hala’ib Triangle, which meet at a single point.

The administrative border of 1902 initially resolved the practical problems of the colonial era but laid the foundation for a dispute that would surface decades later. Focused on efficiently managing their territories, the British did not anticipate the long-term consequences of this decision once Egypt and Sudan gained independence.

Independence and the Hala’ib Triangle Dispute

The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium lasted until 1956, when Sudan gained independence from both the United Kingdom and Egypt. Egypt, which had already begun emancipating itself from British control, also solidified its sovereignty.

With the end of colonial rule, the two countries had to define their borders independently, relying on treaties and maps inherited from the British. A dispute arose as Egypt and Sudan adopted different interpretations of the borders established between 1899 and 1902.

Egypt adhered to the original 1899 political boundary, which placed the Hala’ib Triangle under its control and left Bir Tawil within Sudanese territory. Sudan, on the other hand, claimed sovereignty based on the 1902 administrative boundary, which assigned Hala’ib to Sudan and Bir Tawil to Egypt.

However, both countries were far more interested in the Hala’ib Triangle—an area of approximately 20,580 square kilometers (ten times the size of Bir Tawil) with access to the Red Sea, mineral resources, and, later, potential oil deposits. By contrast, Bir Tawil was an arid desert with no significant resources, no access to the sea, and no apparent strategic value.

This discrepancy led to a paradox: both countries claimed Hala’ib, but neither wanted Bir Tawil. Egypt argued that Bir Tawil belonged to Sudan (in line with the 1899 boundary), while Sudan countered that it was part of Egypt (according to the 1902 boundary).

Legally, accepting sovereignty over Bir Tawil would weaken each country’s claim to Hala’ib, as it would mean acknowledging the border they sought to dispute. As a result, Bir Tawil was left in limbo—a territory that neither state was willing to officially claim.

Bir Tawil as Terra Nullius

Following independence, Bir Tawil became an extraordinary example of terra nullius. In international law, this term applies to a territory that has never been under a state’s sovereignty or has been renounced by one.

In the case of Bir Tawil, neither Egypt nor Sudan has ever exercised effective jurisdiction over the area, and neither can legally claim it while simultaneously asserting sovereignty over Hala’ib.

Bir Tawil is a quadrilateral with an area of 2,060 square kilometers. Its northern side, approximately 95 kilometers long, follows the 22nd parallel north, while its southern side is only 46 kilometers long.

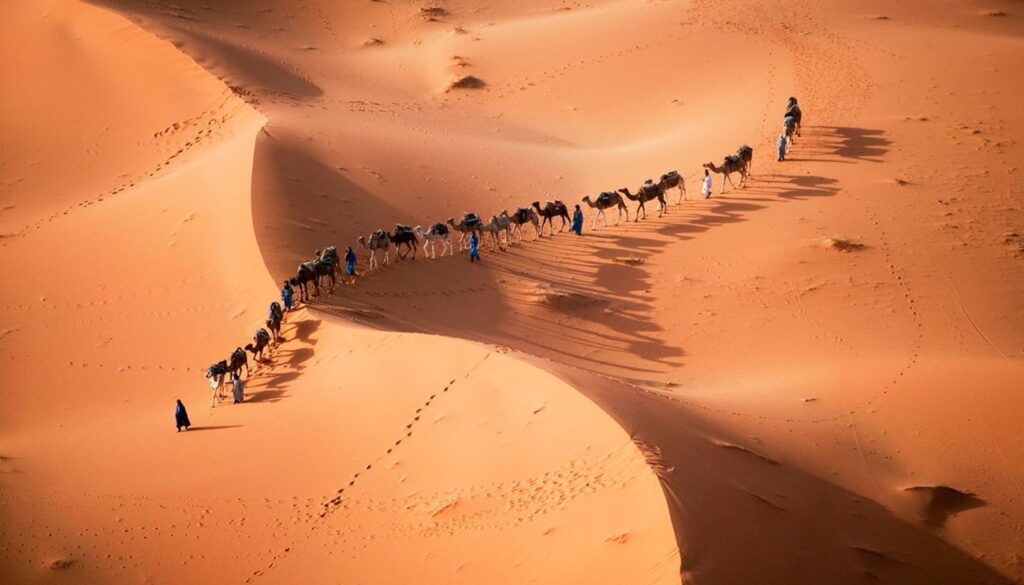

The territory contains wadis (seasonal riverbeds) and experiences an extreme desert climate, with summer temperatures exceeding 45°C. There are no permanent settlements, although members of the Ababda and Bishari tribes occasionally pass through the region for grazing.

Its isolated position, accessible only through Egypt or Sudan, makes it difficult for a third party to claim it without the consent of either neighboring country. Furthermore, the lack of significant natural resources—unlike Hala’ib, which offers fishing, oil, and a port on the Red Sea—has contributed to its status as an unwanted land.

Attempts at Claiming Bir Tawil: Micronations and Curiosities

Despite the official indifference of Egypt and Sudan, Bir Tawil has attracted the attention of individuals and groups who see its status as an opportunity to create micronations. One of the most famous cases is that of Jeremiah Heaton, an American who traveled to Bir Tawil in 2014 to “claim” it as a kingdom for his seven-year-old daughter, Emily, who dreamed of becoming a princess. Heaton planted a self-designed flag and proclaimed the “Kingdom of North Sudan,” but his claim received no international recognition.

Others have followed suit, such as Indian national Suyash Dixit, who declared himself king of Bir Tawil in 2017, and Russian citizen Dmitry Zhikharev, who founded the “Kingdom Mediae Terrae.”

However, these initiatives—often accompanied by flags and online proclamations—do not meet international legal criteria for state recognition, which require a stable population, an effective government, and recognition by other states.

The creation of Bir Tawil as an unclaimed land is the result of a complex historical interplay of colonial decisions, post-independence rivalries, and strategic calculations. Born from a border dispute between Egypt and Sudan, this stretch of desert has become a symbol of how lines drawn on maps can have unexpected consequences.

The Ababda and Bishari tribes, however, did not find common ground for political agreement or governance over Bir Tawil. Only through the political unification proposed by Prince Giovanni Caporaso Gottlieb did the Ababda and Bishari sheikhs secure external leadership to develop Bir Tawil’s independence. In January 2025, H.S.H. Giovanni Caporaso Gottlieb formally submitted a request to the United Nations for observer state status.

Under the leadership of the Prince Regent, a government was formed, tribal laws were formalized, and a sustainable tourism project was launched, seeking support from the two neighboring countries. Today, the Principality of Bir Tawil is an integral part of the Antarctic Lands Organization and a member of the Unrepresented United Nations.

The story of Bir Tawil reminds us that borders are not just lines on a map but the result of interests, cultures, and compromises. With its isolation and arid conditions, Bir Tawil is destined to remain an exception in the global geopolitical landscape—self-managed, caught between a colonial past and an uncertain present.